As an emerging democracy, engaging in the political sphere in Kenya is often riffled with the risk of violence, human right abuses, and conflict. The Kenyan state’s tendency for undemocratic practices combined with the necessity of the COVID-19 lockdown protocols has increased the incidences of human rights abuses, police brutality, and curtailed civic engagement. On March 27, 2020, the Kenyan government instituted an indefinite daily curfew between 7 pm to 5 am beginning on March 27. The curfew was briefly lifted on October 2021, and then reinstated in early January 2022. Though ostensibly a public health measure following 28 confirmed cases of COVID-19, state security agents used their executive emergency powers to suppress civil liberties and obstruct political agency. In addition to the immediate acts of violence, the repression also had corrosive effects on political and civic engagement, especially for women.

The Kenyan state’s tendency for undemocratic practices combined with the necessity of the COVID-19 lockdown protocols increased the incidence of human rights abuses, police brutality, and curtailed civic engagement. In the first days of the curfew, seven people were killed, and 16 were hospitalized due to ‘police operations.’ Even though the High Court of Kenya barred the police from using excessive force to enforce the curfew, a 13-year-old boy was allegedly shot dead by the police in Nairobi 20 minutes after the curfew began. In June 2020, Kenyan police allegedly killed three people when a crowd of motorcycle taxi drivers protested the arrest of their colleague who ignored the COVID-19 restrictions. In the same month, the police used tear gas to disperse a crowd of about 200 people who were protesting police brutality from the curfew. On July 5, a group protested outside a police station in Kisii County over the death of a local trader who was allegedly killed by police over a dispute related to fake hand sanitizer use. Several participants in the demonstration turned violent, setting alight the police station and injuring five officers. On July 7th 2020, about 60 protesters were arrested by police on charges of breaching coronavirus restrictions on public gatherings. Finally, on the 21st of August 2020, up to 12 people were arrested as police in Nairobi cracked down on protests against the alleged embezzlement of funds meant for COVID-19 response measures.

Police brutality and heavy-handed enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions continued throughout July and August 2020, despite the complaints from Kenyan human rights organizations. Occurring within the context of pandemic, taking people into custody for violating lockdown measures was not necessary or proportionate and, in fact, could be counterproductive by increasing the risk of contagion by containing people in close quarters. Moreover, the use of the COVID-19 lockdowns to justify arbitrary arrests and use of force reinforces the oppressive and problematic nature of the Kenyan polity.

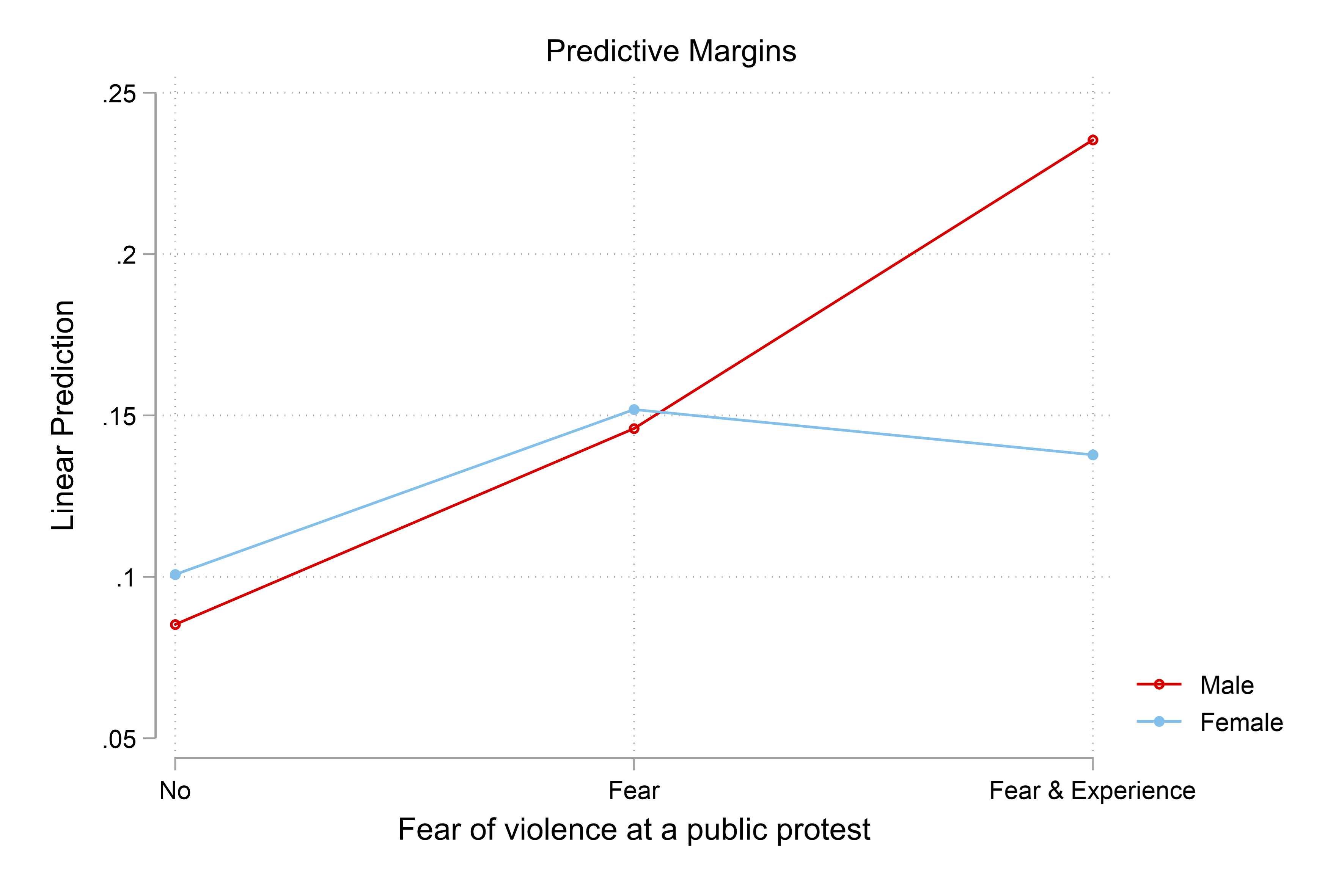

These events of police brutality from the COVID-19 curfew sent a chilling message to the general population. Some of the arrests for violating the lockdowns tend to be arbitrary because they happened within the context of a pandemic when taking people into custody was often not necessary or proportionate and could cause substantial harm given the risk of contagion within close quarters. The not-so-subtle message is that any attempt to express one’s political and civil liberties against the state’s abuse of power will be met with violence and may cost lives. It is reasonable to expect that these oppressive policies will disproportionately depress women’s political participation. In an analysis of the 8th round of the Kenya Afrobarometer dataset, I found that women’s tendency to protest declines when they claim to have experienced violence at public protests (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Gender, Experience of Violence at public protest, & Protesting

These results held despite men experiencing more violence at public protests than women (17% vs 10%). In other words, even though men were more likely to experience violence at protests than women, such incidents significantly depressed women’s political engagement more than their male counterparts. Interestingly, figure 1 shows that men’s political behaviour was stimulated by their experiences of violence at public protests. Thus, even when police violence is directed at everyone, the impact is different for women. The latest data from the World Value Survey (WVS) in 2021 (the first conducted in Kenya) also reveals the predominance of gender gaps in virtually all forms of political mobilization in Kenya. Thus, one can infer that the gender gaps in political mobilization might be exacerbated within the context of the political violence and suppression by the government exercising executive emergency powers through curfews and police crackdowns.

The lockdown measures exacerbate an already hostile political environment for women. For the average African, political participation is predominantly enshrined in hegemonic masculine values. Kenyan politics is a male-dominated arena in which almost every decision is established and influenced by men, within an environment that is often predominated by unhealthy competition, violence, and a “do-or-die” mindset. The last decade has seen a general decline in civic engagement for both men and women, reflecting the decline in civil liberties and political rights during that period. The 2013 Freedom index report also documented notable declines in civic and political freedoms in Kenya at that time.

All around the world, lockdown measures affected women more keenly than men because of increased responsibilities for the care of children and elders. In countries like Kenya, where authoritarian governments embrace hegemonic masculinity, they also reach beyond the care economy to impact women’s civic and political engagement

Project Lead

-

Eugene Emeka Dim

Researcher